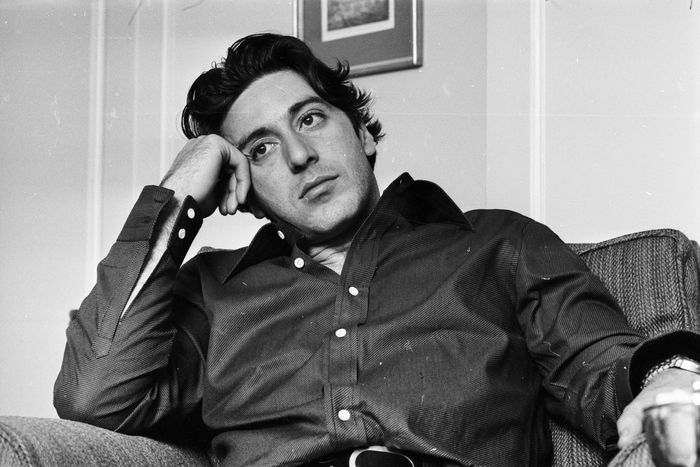

It can be difficult to reconcile the disparate versions of Al Pacino. When he emerged in the 1970s alongside the other brooding, intense leading men of the New Hollywood — including Gene Hackman, Dustin Hoffman, and quasi rival turned onscreen soulmate Robert De Niro — Pacino seemed to fit right in. Already in his 30s and a Tony winner who had put in time at the Actors Studio, he arrived in Hollywood ready to rip through a run of tightly controlled performances. His hangdog eyes could communicate anything from beneath the surface, be it the exhausted paranoia of Frank Serpico or the caged animal threatening to explode out of Sonny Wortzik in Dog Day Afternoon. But with 1983’s Scarface, Pacino swerved away from his contemporaries toward the operatic, carving out a lane for himself as the guy who often goes big in ways that both thrill and confound. He went electric, and has continued to reveal new versions of himself ever since, building out an iconography in the back half of his career that may prove as durable, in its own way, as that of his early work — from “hoo-ah” to Dunkaccino to “Solidarity!,” not to mention a few paycheck roles along the way.

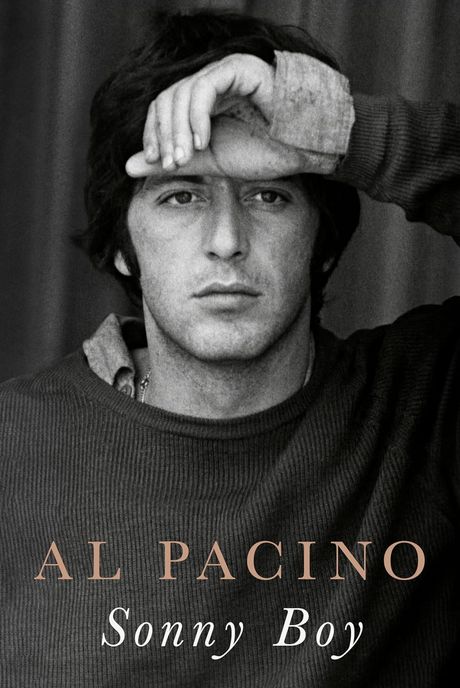

Pacino’s new memoir, Sonny Boy, is a 363-page attempt to make sense of all that, drawing a through-line from the rambunctious kid getting chased by cops across the South Bronx to the octogenarian Hollywood icon dancing down the streets of Beverly Hills. His childhood serves as a framing device, with the actor crediting his single mother with keeping him off the streets enough to avoid the grim fate of his beloved neighborhood crew. The rest of his life, he writes, has been a “moon shot,” and the book ambles along in wide-eyed amazement at everything that’s happened to Pacino. At its best, reading it feels like pulling up a stool next to the actor as he unspools one anecdote after another, often beginning with charmingly vague table-setting about how “one day” he bumped into Marty Sheen on the subway. That tone reaches its limits when Pacino broaches difficult topics before retreating from them — not giving his kids enough attention when they were young, for instance, or long-ago diva behavior that might be compelling to draw the psychological curtain back on.

Even so, we’re not here for a therapy session so much as a glimpse into the idiosyncratic mind of our most mercurial movie star, who’s more than happy to wax poetic about the lifesaving qualities of Chekhov or to share his imagined conversations with Bertolt Brecht. Sometimes that’s enough. Below are six takeaways from Sonny Boy.

Not even Pacino can make sense of his ’70s miracle run

Early in the book, in a moment that will surely be in the eventual Pacino biopic, the actor’s mentor, Charlie Laughton, says to him, “Al, you’re going to be a big star.” “I know, Charl. I know,” Pacino responds. That exchange foreshadows a recurring theme: Pacino knows he’s going to make it as an actor because he has to, and yet success continually blindsides him. When The Godfather launches him out of a cannon in 1972, Pacino describes feeling detached from the fame it brought him — the best he can do to explain his own success is to tip his hat to those around him, including longtime manager Marty Bregman and Francis Ford Coppola, who advocated for Pacino when the studio heads wanted a more established star.

At times, the book makes you long for clearer insights into Pacino’s craft, even if the secret of his best performances lies in the unconscious, as he said in his recent New York Times interview. His performance in Dog Day is one of the great marvels of screen acting, and yet the most tangible explanation Pacino offers is that he came to set one day after a long night spent pacing his room while chugging wine and began playing the character “antsy, animated, and agitated.” Sidney Lumet, the film’s director, somehow says more about its particular alchemy with an even vaguer statement: “This thing is out of our hands, Al.”

On making Jackie Kennedy kiss the ring

In one of the most baffling passages of the book, Pacino describes going back to his dressing room one night after a performance of Richard III in 1979 and sitting “bone-eyed and out of it” in his “little armchair.” He looks up, and Jacqueline Kennedy is standing in front of him with her daughter. As he stares up at the former First Lady, Pacino holds out his hand for her to kiss it. He declines to share what happened next, but he does admonish himself: “Please tell me, what’s wrong with me?” I don’t know, Al! The only justification he can muster is that a self-absorbed actor is liable to do anything after performing one of the greatest plays of all time.

Other instances of diva behavior crop up, but Pacino contends that stars were often labeled “difficult” for using their clout to make a better movie. In Scarface, for instance, he pushed for the “Say good night to the bad guy” scene to be filmed as written, in a fancy restaurant (i.e., an expensive additional location), to contrast Tony Montana’s vulgarity against the high society he’ll never be a part of. (He was right to do so.)

Pigeon shit and passion projects

As is often the case with celebrity memoirs, Pacino spends a lot of time on underseen passion projects, like his hybrid documentary Looking for Richard. While filming up by the Cloisters, he opts against filming on the roof of the Cathedral of St. John the Divine because it’s covered with pigeon shit, which he had heard was “extremely poisonous.” (Which is somewhat true, apparently.) Who should he run into that day but the tightrope walker Philippe Petit, who says, “So it’s poison. If an actor dies, he dies for his art.”

Diane Keaton helped save him from financial ruin

Among his many talents, Pacino seems to be adept at going broke, as he admits in Sonny Boy. After a few years away from the movie business in the late ’80s, he found himself with too much money going out and none coming in, and his then-girlfriend, Diane Keaton, dragged him to his entertainment lawyer when she realized how bad it was. Pointing to Pacino, Keaton told the lawyer, “He’s an ignoramus. When it comes to this, you’ve got to take care of him.” After that, she found the Sea of Love script for him, and Pacino was on his way back to the top, baby.

On the drug he “never touched” and overacting

Pacino wants to set the record straight: He’s apparently never done cocaine. “It may surprise you,” he writes, “to know I’ve never touched the stuff,” explaining that he’s always had an abundance of energy, and that playing Tony Montana provided him with an additional “liberation.” In regard to overacting, Pacino addresses it on a case-by-case basis: Some movies call for it, like Scarface. In Heat, his performance would make more sense if Michael Mann hadn’t cut a shot of Vincent Hanna doing a key bump, implying that he’s on cocaine for much of the film. In Scent of a Woman, well … he may have gone too big, but he “could do it better now.”

On mortality

Late in the book, a current-day Pacino takes a look in the mirror, assesses the “old wolf with a snarl” staring back at him, and says, “Is that still you, Al?” It’s a quietly stunning little moment — an acknowledgment of everything that’s gone, never to come back, wrapped in a bit of self-deprecation from a guy who’s not too humble to call his younger self “pretty.” For someone who’s lost a lot of people along the way (all three of his main neighborhood buddies died young, as did his mother), Pacino seems perplexed by the concept of age, as if the fact that he still has so much energy at this point in life should have stopped the clock somewhere along the way. Even now, though, he knows what gets him up in the morning. “When you’re a certain kind of person, these things keep us going,” he says, referring to his planned film adaptation of King Lear. “These passion projects literally keep us alive.”