Walton Goggins has had leading roles before. He’s played charismatic baddies and “but I can fix him” dark-horse boyfriends; he’s explored cowboy tropes of the American West and become the good-guy straight man. His role as The Ghoul in Fallout (and his preapocalypse identity as Cooper Howard) combines all of it. He’s the bad dude and the hero at the same time. He has been transformed into something unrecognizable, and yet it’s an immediately recognizable Goggins performance. He’s a rogue traversing the remnants of a postapocalyptic California, and he’s improbably hot despite — or maybe, somehow, because of? — his notable noselessness.

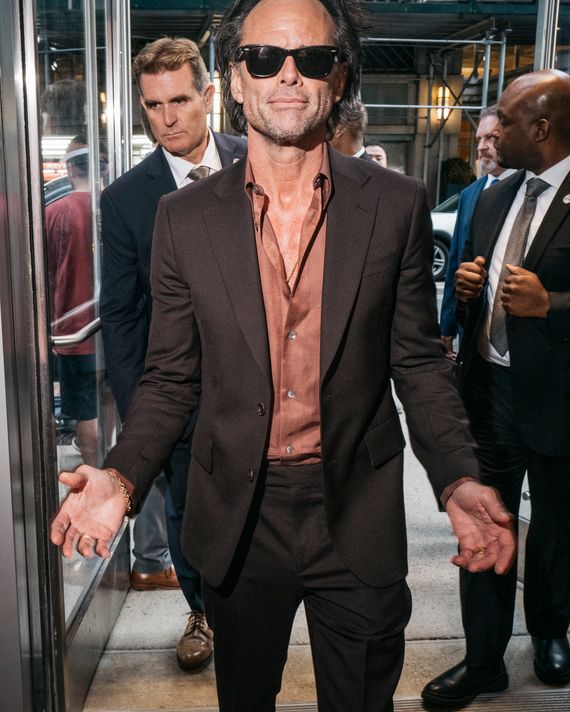

In a conversation we hosted earlier this week following a screening of Fallout’s finale at the the SAG-AFTRA Foundation Robin Williams Center in midtown Manhattan, Goggins explained he was so eager to work with Fallout EP Jonathan Nolan that he agreed to the role before learning he would lose the facial feature. “He said, ‘Okay, well, we want you to play this irradiated kind of cowboy who’s been walking a postapocalyptic wasteland for 200 years, and he doesn’t have a nose,’” Goggins remembers. “And I said, ‘Hey, you know what? Maybe I should read those scripts.’ And I read them and was just so taken with it.”

How did you became involved with this show? My understanding is that you very much wanted to work with Jonathan Nolan, yes?

Walton Goggins: I got a phone call from my agents that Jonathan Nolan wanted to get on the phone with me with these two writers: Geneva Robertson-Dworet, who is a friend of mine — I did Tomb Raider with her — and Graham Wagner, whom I’ve been a fan of for a very, very long time. And two minutes into the conversation, I said, “I’m in.” They said, “Well, don’t you want to know who you’re playing?” I said, “It’s irrelevant. Doesn’t matter.” “Well, don’t you want to read a script?” “Sure, whatever.” And then he said, “Okay, well, we want you to play this irradiated kind of cowboy who’s been walking a postapocalyptic wasteland for 200 years, and he doesn’t have a nose.” And I said, “Hey, you know what? Maybe I should read those scripts.” And I read them and was just so taken with it, really in the first 30 minutes.

What was happening in those first two minutes of conversation where you were in before you knew about the nose?

I love Memento and Westworld and all the movies Jonathan has written, and I’m just a very, very, very big fan of his.

There are two characters that you play, different versions of the same person. Could you talk about how westerns play into how you see both The Ghoul and his early-life version?

I’d have to start this conversation by talking about the first seven or eight pages I read, which was the opening of the series, and how it takes us from the life we knew before the bombs were dropped to actually dropping the bombs. I was so viscerally moved by that on the page; that experience, for me, in my imagination, thinking about playing it, and then, like you said, reading as the show progressed and understanding that they were touching on these themes of The Good, the Bad and the Ugly and moral ambiguity, the good guy becomes the bad guy becomes the good guy.

I love that genre and watched a lot of movies that I have seen before in preparation for this, really kind of looking not so much for The Ghoul, even though that was a part of it, but Cooper Howard. He is a 1950s western-movie star. So I really wanted to understand who his contemporaries were. What jobs did he lose out on? What jobs did he get? You know, the man —

Do you know what jobs he lost out on?

I believe Cooper Howard came to Hollywood from the middle of America, probably Oklahoma, from a good family. He wasn’t escaping or running away from anything. He’s just a guy that came out and could ride a horse, and somebody saw him and said, “Well, hey, you should do this for a living.” And he did it, and he’s just the kind of guy who you want to hang out with.

He’s got a great sense of humor, and a real ease about him as a person, and an actor didn’t show up for work one day, and the director said, “Hey, could you say a couple of these lines?” And he said, “Yeah, okay. How much does that pay?” Yeah, it pays a lot better than riding a horse. And he was good at it. And then he got another job and another job and lo and behold, then he has a career.

Do you usually build backstories like that for your characters?

Without getting too much into process, it’s just the school that I went to. I don’t look at it as backstory, because then that’s a step removed from the process. So then you would have to be, first and foremost, an actor playing a character writing a backstory for the character that you’re playing. And I just skip all of those steps.

My teacher, and the way he talked about this process is — it’s a child’s game. You hold up a mirror to nature and you turn yourself over to an imaginary set of circumstances. It’s really that simple, and it’s that complicated, right? Because your ego really has to get out of the way. So, instead of writing down these things, I just read the script 250 times, like Anthony Hopkins. That’s where I got it from.

If you’re going to take from somebody, Anthony Hopkins seems —

You take from him, and that’s who my teacher talked about, and I got the opportunity to ask Tony when we worked together a long time ago. And over the course of reading it, the words cease to exist and you are, all of a sudden, living in a world that transcends the words. Right? And then your imagination just goes wild. It could be anything. That’s really my jumping-off point. And I do that with everything.

So, you know every moment of Boyd Crowder’s childhood also?

You know, I do. Yeah. Maybe not every moment. Some of those moments, no one wants to know about. But, yeah. I know a lot of them.

But you are playing this character at two very different moments in his life. Does that process change when you’re approaching these different elements? Or are you having to think about that play process differently when you’re thinking, he’s here versus he’s now in this apocalyptic wasteland? Or is it essentially just coming to the script in the same way?

God, I’d love to see someone else play this character. It would be great if it was a play. I’d just like to see three or four other actors step in there, just to see how they would do it differently. For me, reading it for the first time and then reading it over and over again, what I realized is that I had to understand who Cooper Howard was to understand fully everything that The Ghoul had lost.

And what that life was really like for Cooper Howard. How much he loved his daughter, and how much he loved his wife and his family and his group of friends. And then building from there. Whenever you say, on paper, Oh, he’s been alive for 200 years. That’s hard to wrap your head around. It’s like, okay, well, really? Has he been alive for 200 years? I don’t think about it in those terms. It’s like, let’s break down these 200 years. What does that really look like?

Day one: What happened in the moment after the bomb dropped? Did he wake up five days later? Did he get up immediately? Three days later? Is his daughter alive? Was she dead? I had my ideas about that, but I still don’t know, and that’ll be explored in the story. Then I thought, what was it like the first time somebody tried to kill him for food or water, for resources? Right? What was it like the first day he had to kill someone for those very things? And the disintegration of a true morality — what is your true north? And the disintegration of everything he knew. He comes from a moral into an amoral existence.

I wrote down a couple of quotes you have said about the makeup: “extremely anxiety provoking,” “extremely uncomfortable,” and “I scared the shit out of myself.”

And we get to do it again! So excited. I mean, it’s different becoming a woman than it is becoming an irradiated ghoul.

Yeah, Sons of Anarchy.

I did a similar process for a friend of mine’s movie down in South Africa, when we were doing Tomb Raider and they just happened to be filming it down there. I only did it for three or four days, and I did the application three or four times, and I hated it. I couldn’t stand to look at myself in the mirror. I had to cover the mirror. The process of sitting still for that long and then carrying the weight of that around, it’s a lot.

So, it was a mind-set. We get there three hours before everyone else, and the process begins, and it’s me and my buddy Jake Garber, and we start putting on the pieces, and then you just have to work through it. I’m a person who likes to move, and this required being still for a long period of time. So we just watched movies every morning.

What movies did you watch?

The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, Rio Bravo, Cheyenne, all of Leone’s stuff, two or three times. The Wild Bunch.

And that makes it into The Ghoul, I imagine.

Well, you know, the one that really spoke to me was Henry Fonda in Once Upon a Time in the West. He was so cool, you know? He’s so quiet and cool, and didn’t waste a lot of energy with movements, and The Ghoul doesn’t, either. And I thought, okay, well, that’s something I can work with. And then, you know, watching Butch Cassidy again and seeing what a rascal Paul Newman is. I mean, it’s Paul Newman. And I thought, Oh, well, that’s an interesting balance between those two worlds. It was between those two that I felt like, yeah, this makes sense to me.

You work a lot with Ella Purnell.

I do.

Lucy and The Ghoul feel like they are starting at very opposite ends of a spectrum and working their way into a middle space. What were the conversations with her, as you were talking about those scenes where your characters are playing against each other?

The truth is, we didn’t talk about it. We didn’t really rehearse anything beyond one scene that we read before we started. And Ella has her process. Her process is different than mine. But I knew we would find our way, and she was such a joy to work with. You couldn’t start from two points on a map that are that polar opposite, right? This is a person who was left to die on the surface, and this other person, her morality is based on one of convenience. So, we didn’t really talk about it. Every day and every scene just kind of happened organically. And Jonathan works really quickly, so there’s not a lot of time to think about it in those terms. And we got to know each other, but I think maybe both of us intentionally didn’t get to know each other until the ending, until we finished.