This list was originally published on April 5, 2018. It has been updated to include Megalopolis.

Over the many phases of Francis Ford Coppola’s half-century-long career — the freewheeling ’60s, the epic visions of the ’70s, the Hollywood misadventures of the ’80s and ’90s, the highly personal experimentation of the aughts — the most common thread is an Italian-American telling the story of America from those on the outside looking in. The Corleones of The Godfather trilogy are the most prominent example, but there’s also the hippies of Missitucky in Finian’s Rainbow, the uprooted housewife in The Rain People, the Oklahoma greasers of The Outsiders and Rumble Fish, the health-care casualties of The Rainmaker, and the soldiers of Apocalypse Now and Gardens of Stone, who weren’t fortunate enough to opt out on bone-spur deferments. And the biggest fringe-dweller of all is Coppola himself, who was determined to make art inside the Hollywood system that constantly pushed him toward compromise — or out the door altogether.

Ranking Coppola’s 23 features — his 1962 soft-core Tonight for Sure is not included, nor is his misbegotten New York Stories short feature or the Disney attraction Captain EO — was a difficult proposition. His ’70s peak was also the peak of the ’70s, but putting masterpieces like the first two Godfather movies, The Conversation, and Apocalypse Now in preferential order is a torment, because they could be ranked differently on any other day. The rest fall under what we’ll call “the S.E. Hinton Conundrum,” in honor of The Outsiders and Rumble Fish, two very different Hinton adaptations that Coppola made in the same year. What to rank higher, the Coppola films that are more conventionally satisfying pieces of craftsmanship, like The Outsiders? Or the audacious messes that often happen when the director tries to reinvent himself, like Rumble Fish? On balance, we rewarded the experiments — even if critics and audiences at the time were far less charitable toward them. His latest (and perhaps last) film, Megalopolis, certainly fits in the latter category — it’s exactly the sort of inspired fiasco that only Coppola would have the nerve to attempt.

Jack is the worst, though. On that point, we can surely agree.

23.

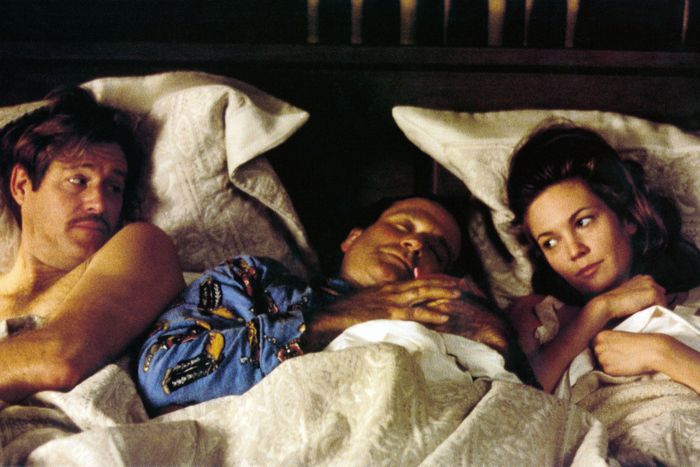

Jack (1996)

The only flat-out indefensible film in Coppola’s career, Jack serves mainly to underscore all the ways in which Big could have gone horribly wrong. As a 10-year-old trapped in the body of a hirsute 40-year-old, Robin Williams is playing a character who isn’t aspiring to be older, like Hanks in the earlier film, but a lonely, awkward, lumbering kid who’s seized by alternating bouts of hyperactivity and deep insecurity. What makes Jack so disturbing is how often this man-child is confronted by adult sexuality: He has a sexy mom (Diane Lane), a sexy teacher (Jennifer Lopez), and a sexy single parent (Fran Drescher) who’s constantly hitting on him, and he makes new friends by buying Penthouse magazines. (And this is all before the retrospective horror of Bill Cosby in a major role.) There’s some glimmer of Coppola in the image of childhood innocence preserved in an adult body, but you have to squint to see it.

22.

Dementia 13 (1963)

Many great directors have graduated from the Roger Corman school of filmmaking, but Coppola’s directorial debut — no, we’re not counting his soft-core movie Tonight for Sure — was more like a crash course. Working over nine days in Ireland with the chump change left over from another Corman production, Coppola was asked to do a no-budget Psycho and delivered a film that Corman had to reshoot to deem releasable. To say Dementia 13 is rough around the edges is an understatement, but Coppola’s script does rework Psycho cleverly, following a widow (Luana Anders) who travels to an Irish castle to work her way into her late husband’s inheritance, but encounters a raft of dark family secrets instead. He also pulls off a couple of striking sequences, like the husband dying as a radio warbles a rockabilly song en route to the bottom of the lake or the resurfacing of a dead girl’s old toys to trigger a psychological breakdown.

21.

Gardens of Stone (1987)

Coppola intended this soppy military drama as a companion to Apocalypse Now, a Vietnam coming-home story that follows the dead bodies and shattered souls from the surreal horror show of the war as they’re laid to rest — or, if alive, put out to pasture — on the peaceful grounds of Arlington National Cemetery. Gardens of Stone gets an extraordinary performance from James Caan as a career military man who can’t hide his misgivings about the war, and Caan shares a wonderfully salty camaraderie with James Earl Jones as his old Korean War buddy and steadfast superior. Yet the spark of inspiration that made Apocalypse Now so vibrant and unpredictable is snuffed by a turgid obsession with military ritual. Coppola captures the ambivalence of officers continuing to honor the fallen during an unjustifiable and unwinnable war, but the drama is buttoned-up and square.

20.

Finian’s Rainbow (1968)

Many Hollywood films of the mid-to-late ’60s were trying to reconcile the escapist gloss of traditional studio entertainment with the onset of dramatic social and political change, but few wear that struggle as awkwardly as Finian’s Rainbow, which gives mid-century Broadway musical a hippie makeover. Coppola coaxed Fred Astaire out of retirement to play a happy-go-lucky Irishman who buries a pot of gold in a valley near Fort Knox under the conviction that his stash will multiply in the verdant soil. Look past the cheery artifice of the setting and musical numbers, however, and Coppola has imagined a very contemporary confrontation between a diverse, idealized commune and the nefarious cops and politicians eager to shut it down. Finian’s Rainbow fantasizes about radical change, but in a filmic language that’s anything but.

19.

Twixt (2011)

The worst of Coppola’s recent(ish) foray into semi-experimental independent cinema, Twixt is nonetheless a fascinating journey into his personal and cinematic past, evoking both the down-and-dirty genre feel of Dementia 13 and the death of his son Gian-Carlo in a boating accident. Shooting a select few sequences in 3-D — the audience is asked, charmingly, to put their glasses on — and the rest in a shadowy, color-drained digital sheen, Coppola casts Val Kilmer as a “bargain-basement” Stephen King who turns a poorly attended small-town book signing into an opportunity to write a local murder mystery that’s still unsolved. Twixt is a peculiar, half-realized doodle of a film, but a minor treat for Coppola completists, who can swim in the references to Corman, Edgar Allan Poe, William Castle, and Nosferatu and appreciate the whole exercise as a series of footnotes to a rich set of a career.

18.

Megalopolis (2024)

Over four decades in the making, Coppola’s dream project about the rebuilding of a major American city after a devastating catastrophe now looks like the swan song of an iconoclast who’s never been afraid to invest himself — and $120 million of his own money, in this case — in his own outsize, impossible artistic vision. But there’s a fine line between the exhilarating audacity and madness of Coppola’s Apocalypse Now and the scattershot, scatterbrained science fiction of Megalopolis, which reaches toward the optimistic thought that humankind can create a utopia from the collapse of New Rome but tumbles repeatedly in getting there. Save for Adam Driver’s Shakespearean gusto as an architect at once mercurial and magical, Coppola has little control over performances that veer toward the cartoonish, and the digital effects have a screensaver chintziness that’s missing the lushness of his best work. Nonetheless, Megalopolis is so flush with inspiration and go-for-broke vitality that its great sequences and terrible sequences are equally arresting — and it’s hard to get anyone to agree on which one is which.

17.

Youth Without Youth (2007)

After a decade-long absence from feature filmmaking, Coppola returned with his most difficult and defiantly independent work to date, a fantasy of eternal youth and rekindled love that curdles into a nightmare. Roughly speaking, it’s like an art-damaged The Curious Case of Benjamin Button, following an old Romanian linguistics professor (Tim Roth) in 1938 who gets struck by lightning and finds himself getting younger, much to the consternation of his doctor (Bruno Ganz) and the interest of the invading Nazis. The opportunity to complete his unfinished manuscript initially makes the film seem like a tribute to deadline extensions, but Youth Without Youth twists itself into a metaphysical phantasmagoria on age, consciousness, spirituality, and 20th-century evil. There’s an overabundance of ideas at play, to put it kindly, but Coppola delivered a necessary adrenaline shot to American independent cinema, which could barely rouse itself to leave its Brooklyn apartment.

16.

You’re a Big Boy Now (1966)

Produced as a very expensive MFA project for UCLA, You’re a Big Boy Now is to Coppola as Who’s That Knocking at My Door? is to Martin Scorsese or Greetings and Hi, Mom! are to Brian De Palma, a highly personal rough draft for a brilliant career to come. Based on David Benedictus’s book, the film tracks closely with the impish spirit of those early De Palmas or a low-budget American variation on the hipster comedy of The Knack … and How to Get It. Like a more infantile version of the aimless young man Dustin Hoffman would canonize a year later in The Graduate, Peter Kastner’s virginal hero moves into a Manhattan apartment to find his independence, but can’t escape his overbearing parents (who called him “Big Boy”) and doesn’t have a clue how to deal with women. You’re a Big Boy Now lays bare the terrors and possibilities of a culture in flux, and its loosey-goosey, anecdotal storytelling pays off in weird comic touches, like Kastner roller-skating around the city or a hostile rooster that’s taken up permanent residence on the fifth floor of his building.

15.

The Godfather Part III (1990)

The question of legitimacy — of what it means to be a real American, rather than an immigrant looking from the outside in — has haunted The Godfather series from the opening frame, and The Godfather Part III comments sharply on how far money can go in absolving even the gravest of sins. The film opens with the obscenity of Michael Corleone getting honored by the Vatican in exchange for a nine-figure check, then watches him sink into a tragedy of his own making. Coppola gives the Corleone story a proper and satisfying Shakespearean arc, but the film conspicuously lacks the creative investment of previous two, and the individual subplots don’t have the same pulp kick, either. And while Coppola has taken enough abuse for casting his daughter Sofia in a critical role, her performance really does harm the film: She’s the linchpin of the entire film — Corleone’s sole hope for redemption and his eventual undoing — and it collapses around her.

14.

The Cotton Club (1984)

Still up to his eyeballs in debt from Zoetrope Studios and perhaps looking to restore his diminished reputation, Coppola made a devil’s bargain and reunited with his Godfather team, producer Robert Evans and screenwriter Mario Puzo, for another stylish tale of gangland violence. Like many of his ’80s films, Coppola’s investment in the look and ambiance of The Cotton Club far outstrips his interest in the action itself, which is particularly flat when trying to wedge the the story of an aspirational jazz musician (Richard Gene) into conflicts between gangs and between races. But the director and his artisans have re-created the famed Harlem nightclub so sumptuously that it often doesn’t matter, especially when the camera shifts to the stage and the song-and-dance numbers take over, including the tap-dancing duo of Gregory and Maurice Hines and Lonette McKee doing her best Lena Horne impression. For better or worse, Coppola cannot hide where his true passions lie.

13.

The Rainmaker (1997)

The ’90s roped many a great director into spinning variations on the same John Grisham idealistic-young-lawyer-takes-on-the-system scenario — even poor Robert Altman got in on the action with The Gingerbread Man — but The Rainmaker is better than its middling reputation suggests. Produced from the ashes of the Clinton health-care initiative, the film turns a lawsuit against an unscrupulous insurance company into a rousing argument against a system that fails (and occasionally kills) the sickest among us. Coppola sets up a David versus Goliath scenario between Matt Damon’s green law-school grad and a phalanx of corporate lawyers (led by Jon Voight) that’s both hugely satisfying and a fair reflection of the uphill battle facing health-care reform in the country at that time. A romantic subplot involving Damon and a battered wife (Claire Danes) could have been tossed without anyone noticing or caring, but Coppola knows what it’s like to buck against the system, and the film effectively rails against a then-common injustice.

12.

The Outsiders (1983)

In 1983, Coppola adapted two S.E. Hinton novels for the price of … well … two, starting with The Outsiders, which feels like Coppola’s nostalgia-soaked version of a James Dean drama, full of sensitive bad boys who stand in for a generation of lost, marginalized young people. Set in Tulsa, Oklahoma, in 1965, where a couple of “Greasers” (C. Thomas Howell and Ralph Macchio) go on the lam after killing a member of a rich rival gang called “the Socs,” the film is no more credible a tale of street toughs than West Side Story, and it turns on an unbelievably ridiculous deus ex machina. But it’s unrivaled as a who’s-who of future stars (Matt Dillon, Patrick Swayze, Tom Cruise, Emilio Estevez, Rob Lowe, and Diane Lane) and Coppola’s sympathies are channeled through a beautiful vision of a dust-choked, twilight-streaked Tulsa that seems frozen in time. A sequence where Howell and Macchio are outside a rural church at dusk, pondering a future in which they have no place, is as beautiful as any in ’80s cinema.

11.

Rumble Fish (1983)

If Coppola’s Hinton adaptations were a “one for them, one for me” proposition, Rumble Fish is definitely the “one for me,” given the director’s total disregard for storytelling convention. The patched-together script is more vibe than narrative, casting Matt Dillon as a sensitive street tough and Mickey Rourke as his troubled older brother, whose vow not to participate in gang fights doesn’t diminish his capacity for violence or the beefs that accumulated when he ruled the street. Shot in luminous black and white, with an experimental score by Stewart Copeland, Rumble Fish reduces the conflict to pure abstraction and allows sight and sound to fill in the gaps. The one shock of color comes in the Siamese fish at a pet store, each confined to their own space in the tank or they’d attack each other — and if a mirror was held up, Rourke notes, they’d attack their own reflection. The film hangs on this lovely visual metaphor for precious, self-destructive youth.

10.

Tetro (2009)

In writing his first original screenplay since The Conversation, Coppola turned once again to his own family history to whip up this melodramatic bauble about the tortured rivalry between two brothers and the imposing legacy of their domineering father. Though set in contemporary Buenos Aires, Argentina, where a ship waiter (Alden Ehrenreich) uses a five-day leave to reconcile with his temperamental older brother (Vincent Gallo), Tetro looks like it takes place half a century earlier, thanks to the luminous black-and-white photography, which gives the city a seductive Old World quality. The dynamic between Ehrenreich and Gallo echoes Matt Dillon and Mickey Rourke in Rumble Fish, but the story’s roots in musical and theatrical ambition bring it closer to Coppola’s heart and inspires him to celebrate the city’s cosmopolitan beauty. His level of investment in the drama itself may be thin, but Buenos Aires hasn’t sparkled so seductively since Wong Kar-wai’s Happy Together.

9.

One From the Heart (1982)

Now here’s the film that broke Coppola, spiritually and financially, an expensive fiasco that he bankrolled heavily through Zoetrope Studios and which recouped the tiniest fraction of its production costs. It’s tempting to say that critics and audiences at the time had it wrong, and that the mix of kitchen-sink domestic melodrama and glittering Hollywood artifice in One From the Heart represents a thrilling reinvention of the musical. But the film doesn’t work: Teri Garr and Frederic Forrest can’t sell the stormy marriage that carries them into the Las Vegas night and Tom Waits’s bluesy songs, performed in non-diegetic duet with Crystal Gayle, are weirdly detached from the action. And yet only a true artist could fail as spectacularly as Coppola does here: With Vittorio Storaro as his cinematographer and Dean Tavoularis on production design, Coppola’s Vegas is a soundstage marvel that bursts with primary colors and romantic possibility. Would that more conventionally “successful” films dream this big.

8.

Peggy Sue Got Married (1986)

A year after Back to the Future, Coppola continued to work his way out of Zoetrope debt by making another time-travel story about returning to the past and sorting out the present. In this case, the role of studio hand suited Coppola, who brings a pleasing air of nostalgia to the 1960 small-town setting and hands most of the film over to Kathleen Turner, who returns to the lusty comic brashness of her Romancing the Stone performance. Whooshed back to the past during her 25-year high-school reunion, Turner’s Peggy Sue has to consider the serious question of whether she’ll pursue a relationship with a young man (Nicolas Cage) who will disappoint her in marriage, but first, she delights in reuniting with her family and friends, and reliving her lost youth. Eternal youth as a theme started to resonate with Coppola, who would return to it in Jack, Bram Stoker’s Dracula, and Youth Without Youth, but its joys fade into a more sober and thoughtful comedy-drama about living with the choices we’ve made.

7.

The Rain People (1969)

The most overlooked and underrated film of Coppola’s career, this road picture could be considered a feminist analogue to Easy Rider, but it’s considerably more grounded in the everyday restlessness and wanderlust that was gripping the country in the late ’60s. As a housewife who discovers she’s pregnant and hits the road with no destination in mind, Shirley Knight represents women who were feeling confined by traditional gender roles, but she doesn’t know where liberation will take her — or if liberation is even possible at all. Other men make a claim for her sympathies, namely James Caan in a heartbreaking performance as an ex-football star afflicted by a head injury and Robert Duvall as a domineering state trooper. The ending is a total calamity, but The Rain People arrives there through an unpredictable and hazily beautiful survey of the new American landscape and one woman’s intrepid effort to find a new place for herself in it.

6.

Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992)

Yes, Keanu Reeves isn’t the best fit for a 19th-century gentleman, and Anthony Hopkins’s Van Helsing is so hammy he could serve himself for Christmas dinner. And yes, the dialogue and atmosphere is exceedingly florid, courting camp if not crossing that line altogether. Yet Bram Stoker’s Dracula is a feast for the senses, from Michael Ballhaus’s brilliant colors and old-fashioned in-camera effects to Eiko Ishioka’s ornate costumes to the score by Wojciech Kilar, which summons the deepest notes from the orchestra and the chorus. Coppola has been redeemed by technical contributions before, but it was his unifying choice to express the romantic qualities of the Dracula myth as boldly and emphatically as possible, paying off in a gothic horror film that bleeds (and bleeds and bleeds) from the heart. Among the variable performances, it helps that Gary Oldman’s Count is the best one: He’s on the other end of the spectrum from Max Schreck’s gnarled Nosferatu, a melancholy creature who’s carried a curse through the centuries.

5.

Tucker: The Man and His Dream (1988)

At the end of a decade spent wriggling under the studio thumb, Coppola framed the story of inventor Preston Tucker and his amazing 1948 Tucker Torpedo as a stirring metaphor for his own career as a frustrated dreamer. With the Big Three automakers as a stand-in for Hollywood, Coppola offers Jeff Bridges as a beaming visionary who wants to make the gleaming, innovative “car of the future,” but gets undermined by his own board of directors and the SEC, which rings him up on charges of stock fraud. Tucker: The Man and His Dream suggests that American capitalism works to serve entrenched power and mass-scale mediocrity while squeezing out the little guy. It’s a crackerjack piece of entertainment, rolling off the assembly line with all the polish and purr of a Tucker sedan, but it’s also an important personal statement from Coppola about how far his own industry had gone astray in the ’80s. The dream of his own studio was dead, too, but like those 50 Tuckers that made it through production, he clings to the hope that its vision won’t be forgotten.

4.

Apocalypse Now (1979)

In converting Joseph Conrad’s novel Heart of Darkness into a potent metaphor for the carnage and madness of the Vietnam War, Coppola wound up taking the same journey downstream, turning his production into a 16-month quagmire in the Philippines. Coppola’s famous quote about the finished film (“Apocalypse Now is not about Vietnam. It is Vietnam.”) opened him up to ridicule, but in his endeavor to throw money and resources at a project that was open-ended and fundamentally impossible to complete, Coppola offered a more vivid and authentic impression of the war than a more orderly operation could have produced. Apocalypse Now functions like a road movie on water: As Captain Willard (Martin Sheen) and his men head down the river to find the rogue Colonel Kurtz (Marlon Brando), Coppola is free to confront them with all the surrealistic detours he can conjure, from blockbuster set pieces like choppers attacking to the sound of Wagner’s “Ride of the Valkyries” to ghoulish madmen like Robert Duvall’s surf-crazy Kilgore and Dennis Hopper’s drugged-out photojournalist. The reality of the war isn’t of interest to Coppola so much as its psychological texture, and the film succeeds in making a nightmare tangible.

3.

The Godfather (1972)

Coppola’s epic about the Corleone crime family can be remembered in memorably anecdotes and sequences: The head of a prized stallion left in a studio boss’s bed; young Michael Corleone (Al Pacino) executing a double murder at a Bronx restaurant; his brother Sonny (James Caan) getting cut up in a tollbooth ambush; Don Vito (Marlon Brando) suffering a heart attack while chasing his grandson around the garden; the coordinated hits on four rival families during a baptism. That’s the thrillingly rendered pulp of Mario Puzo, who wrote the novel and co-wrote the screenplay with Coppola. But the greatness of The Godfather is rooted in Coppola’s rich understanding of Italian-American culture and how the Corleones are an extreme example of an immigrant family that’s both part of and apart from its adopted home. “I believe in America” is the first line spoken in the film, which then goes on to reveal the yawning chasm between the American Dream as it’s idealized and the cutthroat means by which the Corleone family pursues it outside the law. In their quixotic pursuit of legitimacy, they find only the rot of illicit power.

2.

The Godfather Part II (1974)

A sequel to The Godfather could have traded cynically on Puzo’s bloody gangster stories for cash, but The Godfather Part II is, among other things, the greatest American film about the immigrant experience. The extraordinary shot of a frail, diseased young Don Vito on Ellis Island, looking out on the Statue of Liberty, sets the table for a decades-spanning journey through a country where opportunity is not extended, but seized through violence and dirty dealing. By cutting back and forth between Vito as a young adult, played by Robert De Niro, and the continuing adventures of his son Michael as head of the Corleone family, Coppola captures the toxic inheritance passed along from one generation to the next and the full, tragic dimension of their story. Never one to leave studio money on the table, Coppola expands the scope of The Godfather Part II to visit the worlds of turn-of-the-century New York City, the decadent end of Batista’s Cuba, and a taste of Sicily itself, where Vito returns to settle an old score. But the film is ultimately about what upward mobility in America really entails for the Corleones and the price it exacts on their souls.

1.

The Conversation (1973)

At a 45-year distance from The Conversation, it’s remarkable to think about how much its paranoia about surveillance and government intrusiveness have become an inextricable part of American life, to the point where we voluntarily give away personal information that Harry Caul (Gene Hackman) tears his apartment to pieces to restrict. Recasting the photographic deception of Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blowup for sound, Coppola follows Hackman’s surveillance expert as he pieces together a conversation between a couple in San Francisco’s Union Square and starts to believe something sinister is about to take place. The first in a long line of post-Watergate thrillers that would include The Parallax View and All the President’s Men, The Conversation seizes on the destabilized atmosphere of a country where the official line could no longer be trusted and insidious conspiracies started to flourish. It also doubles as an exceedingly clever film about the filmmaking process itself and the deceptive nature of putting together sound and image. The Conversation keeps looking better year after year because Coppola understood so well where the country was headed. We’re all Harry Caul and his saxophone now, bleating against a world where true privacy is no longer possible.